For other uses, see Excalibur (disambiguation) and The Sword in the Stone (disambiguation).

Excalibur

Excalibur (/ɛkˈskælɪbər/) is the legendary sword of King Arthur, sometimes also attributed with magical powers or associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. It was associated with the Arthurian legend very early on. Excalibur and the Sword in the Stone (the proof of Arthur's lineage) are in some versions said to be different, though in other incarnations they are either the same or at least share their name. In Welsh, it is called Caledfwlch; in Cornish, Calesvol (in Modern Cornish: Kalesvolgh); in Breton, Kaledvoulc'h; and in Latin, Caliburnus. Several similar swords and other weapons also appear in this and other legends.

Contents

2The sword in the stone and the sword in the lake

9References9.1Citations9.2Sources9.3Further reading

Forms and etymologies[edit]

The name Excalibur ultimately derives from the Welsh Caledfwlch (and Breton Kaledvoulc'h, Middle Cornish Calesvol), which is a compound of caled "hard" and bwlch "breach, cleft".[1] Caledfwlch appears in several early Welsh works, including the prose tale Culhwch and Olwen (c. 11th–12th century). The name was later used in Welsh adaptations of foreign material such as the Bruts (chronicles), which were based on Geoffrey of Monmouth. It is often considered to be related to the phonetically similar Caladbolg, a sword borne by several figures from Irish mythology, although a borrowing of Caledfwlch from Irish Caladbolg has been considered unlikely by Rachel Bromwich and D. Simon Evans. They suggest instead that both names "may have similarly arisen at a very early date as generic names for a sword". This sword then became exclusively the property of Arthur in the British tradition.[1][2]

Geoffrey of Monmouth, in his Historia Regum Britanniae (The History of the Kings of Britain, c. 1136), Latinised the name of Arthur's sword as Caliburnus (potentially influenced by the Medieval Latin spelling calibs of Classical Latin chalybs, from Greek chályps [χάλυψ] "steel"). Most Celticists consider Geoffrey's Caliburnus to be derivative of a lost Old Welsh text in which bwlch (Old Welsh bulc[h]) had not yet been lenited to fwlch (Middle Welsh vwlch or uwlch).[3][4][1] In the late 15th/early 16th-century Middle Cornish play Beunans Ke, Arthur's sword is called Calesvol, which is etymologically an exact Middle Cornish cognate of the Welsh Caledfwlch. It is unclear if the name was borrowed from the Welsh (if so, it must have been an early loan, for phonological reasons), or represents an early, pan-Brittonic traditional name for Arthur's sword.[5]

In Old French sources this then became Escalibor, Excalibor, and finally the familiar Excalibur. Geoffrey Gaimar, in his Old French Estoire des Engleis (1134–1140), mentions Arthur and his sword: "this Constantine was the nephew of Arthur, who had the sword Caliburc" ("Cil Costentin, li niès Artur, Ki out l'espée Caliburc").[6][7] In Wace's Roman de Brut (c. 1150–1155), an Old French translation and versification of Geoffrey's Historia, the sword is called Calabrum, Callibourc, Chalabrun, and Calabrun (with variant spellings such as Chalabrum, Calibore, Callibor, Caliborne, Calliborc, and Escaliborc, found in various manuscripts of the Brut).[8]

In Chrétien de Troyes' late 12th-century Old French Perceval, Arthur's knight Gawain carries the sword Escalibor and it is stated, "for at his belt hung Escalibor, the finest sword that there was, which sliced through iron as through wood"[9] ("Qu'il avoit cainte Escalibor, la meillor espee qui fust, qu'ele trenche fer come fust"[10]). This statement was probably picked up by the author of the Estoire Merlin, or Vulgate Merlin, where the author (who was fond of fanciful folk etymologies) asserts that Escalibor "is a Hebrew name which means in French 'cuts iron, steel, and wood'"[11] ("c'est non Ebrieu qui dist en franchois trenche fer & achier et fust"; note that the word for "steel" here, achier, also means "blade" or "sword" and comes from medieval Latin aciarium, a derivative of acies "sharp", so there is no direct connection with Latin chalybs in this etymology). It is from this fanciful etymological musing that Thomas Malory got the notion that Excalibur meant "cut steel"[12] ("'the name of it,' said the lady, 'is Excalibur, that is as moche to say, as Cut stele'").

The sword in the stone and the sword in the lake[edit]

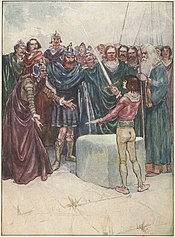

Arthur draws the sword from the stone in Henrietta Elizabeth Marshall's Our Island Story (1906). Here, as in many more modern depictions of this scene, there is no anvil and the sword is lodged directly within the stone itself

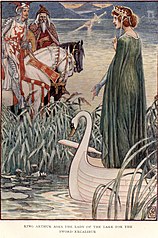

"King Arthur asks the Lady of the Lake for the sword Excalibur". Walter Crane's illustration for Henry Gilbert's King Arthur's Knights: The Tales Retold for Boys and Girls (1911)

In Arthurian romance, a number of explanations are given for Arthur's possession of Excalibur. In Robert de Boron's Merlin, the first tale to mention the "sword in the stone" motif c. 1200, Arthur obtained the British throne by pulling a sword from an anvil sitting atop a stone that appeared in a churchyard on Christmas Eve.[13] In this account, as foretold by Merlin, the act could not be performed except by "the true king", meaning the divinely appointed king or true heir of Uther Pendragon. The scene is set by different authors at either London (Londinium) or generally in Logres, and might have been inspired by a miracle attributed to the 11th-century Bishop Wulfstan of Worcester.[14] As Malory related in his most famous English-language version of the Arthurian tales, the 15th-century Le Morte d'Arthur: "Whoso pulleth out this sword of this stone and anvil, is rightwise king born of all England."[15][note 1] After many of the gathered nobles try and fail to complete Merlin's challenge, the teenage Arthur (who up to this point had believed himself to be son of Sir Ector, not Uther's son, and went there as Sir Kay's squire) does this feat effortlessly by accident and then repeats it publicly. The identity of this sword as Excalibur is made explicit in the Prose Merlin, a part of the Lancelot-Grail cycle of French romances (the Vulgate Cycle).[16]

Eventually, in the cycle's finale Vulgate Mort Artu, when Arthur is at the brink of death, he orders Griflet to cast Excalibur into the enchanted lake. After two failed attempts (as he felt such a great sword should not be thrown away), Griflet finally complies with the wounded king's request and a hand emerges from the lake to catch it. This tale becomes attached to Bedivere, instead of Griflet, in Malory and the English tradition.[17] However, in the Post-Vulgate Cycle (and consequently Malory), Arthur breaks the Sword from the Stone while in combat against King Pellinore very early in his reign. On Merlin's advice, he then goes with him to be given Excalibur by a Lady of the Lake in exchange for a later boon for her (some time later, she arrives at Arthur's court to demand the head of Balin). Malory records both versions of the legend in his Le Morte d'Arthur, naming each sword as Excalibur.[18][19]

Other roles and attributes[edit]

In Welsh legends, Arthur's sword is known as Caledfwlch. In Culhwch and Olwen, it is one of Arthur's most valuable possessions and is used by Arthur's warrior Llenlleawg the Irishman to kill the Irish king Diwrnach while stealing his magical cauldron. Though not named as Caledfwlch, Arthur's sword is described vividly in The Dream of Rhonabwy, one of the tales associated with the Mabinogion (as translated by Jeffrey Gantz): "Then they heard Cadwr Earl of Cornwall being summoned, and saw him rise with Arthur's sword in his hand, with a design of two chimeras on the golden hilt; when the sword was unsheathed what was seen from the mouths of the two chimeras was like two flames of fire, so dreadful that it was not easy for anyone to look."[20][note 2]

Geoffrey's Historia is the first non-Welsh source to speak of the sword. Geoffrey says the sword was forged in Avalon and Latinises the name "Caledfwlch" as Caliburnus. When his influential pseudo-history made it to Continental Europe, writers altered the name further until it finally took on the popular form Excalibur (various spellings in the medieval Arthurian romance and chronicle tradition include: Calabrun, Calabrum, Calibourne, Callibourc, Calliborc, Calibourch, Escaliborc, and Escalibor[21]). The legend was expanded upon in the Vulgate Cycle and in the Post-Vulgate Cycle which emerged in its wake. Both of them included the Prose Merlin, however the Post-Vulgate authors left out the original Merlin continuation from the earlier cycle, choosing to add an original account of Arthur's early days including a new origin for Excalibur. In some versions, Excalibur's blade was engraved with phrases on opposite sides: "Take me up" and "Cast me away" (or similar). In addition, it said that when Excalibur was first drawn in combat, in the first battle testing Arthur's sovereignty, its blade shined so bright it blinded his enemies.[22]

In the later romance tradition, including Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur, Excalibur's scabbard is also said to have powers of its own, as any wounds received while wearing it would not bleed at all, thus preventing the wearer from ever bleeding to death in battle. For this reason, Merlin chides Arthur for preferring the sword over its sheath, saying that the latter is the greater treasure. The scabbard is, however, soon stolen from Arthur by his half-sister Morgan le Fay in revenge for the death of her beloved Accolon having been slain by Arthur with Excalibur in a duel involving a false Excalibur (Morgan also secretly makes at least one duplicate of Excalibur during the time when the sword is entrusted to her by Arthur earlier in the different French, Iberian and English variants of that story); the sheath is then thrown by her into a lake and lost. This act later enables the death of Arthur, deprived of its magical protection, many years later in his final battle. In Malory's telling, the scabbard is never found again; in the Post-Vulgate, however, it is recovered and claimed by another fay, Marsique, who then briefly gives it to Gawain to help him fight Naborn (Mabon) the enchanter.[23]

In some French works, such as Chrétien's Perceval and the Vulgate Lancelot, Excalibur is wielded also by Gawain,[24] Arthur's nephew and one of his best knights; this is in contrast to most versions, where Excalibur belongs solely to Arthur. A few texts, such as the English Alliterative Morte Arthure and one copy of the Welsh Ymddiddan Arthur a'r Eryr,[25] tell of Arthur using Excalibur to kill his son Mordred.

Excalibur as a relic[edit]

Historically, a sword identified as Excalibur (Caliburn) was supposedly discovered during the purported exhumation of Arthur's grave at Glastonbury Abbey in 1191.[26] On 6 March 1191, after the Treaty of Messina, either this or another claimed Excalibur was given as a gift of goodwill by the English king Richard I of England (Richard the Lionheart) to his ally Tancred, King of Sicily.[27] It was one of a series of Medieval English symbolic Arthurian acts, such as associating the crown won from the slain Welsh prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd with the crown of King Arthur.[28]